Amphibian Road Crossing

There are road crossing structures for amphibians migrating to the spawning waters (temporary migration sites) as well as structures for amphibians migrating in both directions (amphibian tunnels). The permanent amphibian tunnels protecting amphibian migration in both directions are the best road crossing structures. The permanent guidance systems with amphibian tunnels are sometimes being extended with temporary amphibian fence panels.

Temporary migration sites

Temporary migration sites based on amphibian fences and trap buckets (cf. Figure 1) should first be controlled along the fence. Walking areas directly along amphibian fences should be kept as clear as possible. Snow, leaves, branches and other debris can interfere with the function of the fence and it can enable amphibians to climb over it, unnecessarily hinder amphibians, or direct them in the wrong directions. Further, ensure that the trap buckets never dry out completely. Damp sponges, damp leaves or damp moss, for example, serve as protection against drying out. One or better two sticks per bucket allow the mice, shrews and beetles to exit. Certain types of mice may be less able to climb than others. Birds such as crows, ravens, buzzards, etc. or mammals such as foxes, otters, martens, polecats, rats, wild pigs, invasive raccoons, etc. can cause problems at a migration site. Therefore, regular care and monitoring is important. The amphibian migration site should be cared for in the morning and evening. If there is tremendous migratory activity, an afternoon care might also be appropriate. Monitoring should also be done on the road. Amphibians on the road should be documented, so the amphibian fence is more likely to be extended or improved. Amphibians are counted for statistics. The amphibians are put directly into the spawning water on the other side of the road, if possible.

Further remarks:

- In some situations a trap bucket with a broad rim is recommended to prevent tree-frogs from climbing out.

- Wire mesh and nets are not recommended as amphibian fence, because amphibians may climb over them. Nets in particular have only limited guiding ability.

- The ends of the amphibian fence should be U-shaped to minimise the number of amphibians leaving the fence.

- The minimum height of the amphibian fence should be 40 cm; in presence of the agile frog the height should be at least 60 cm.

- The upper part of the amphibian fence should be bended to prevent amphibians from climbing over.

- Stakes should not be places on the side where amphibians are moving.

- Magnetising material should not be used, because this could disorient the common toad and other amphibians.

Amphibian tunnels

There are one-way amphibian tunnels and two-way amphibian tunnels. Whereas two-way amphibian tunnels are the conventional amphibian tunnels and can be used better by other animals as well.

One-way amphibian tunnels

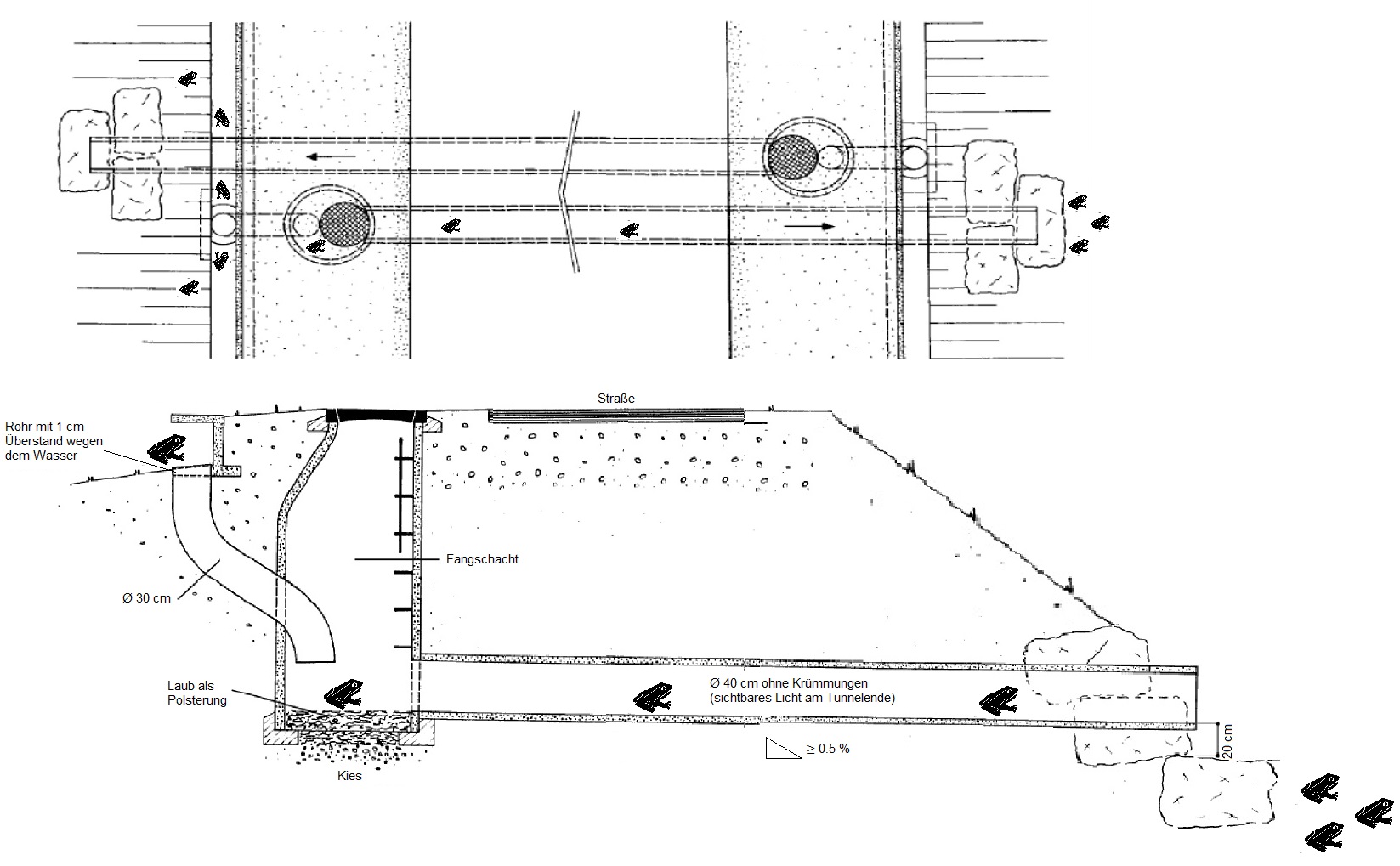

At the one-way amphibian tunnels, the amphibians are led to a trap shaft that forces them to use the tunnel. To cross the road from the spawning water, a second, analogous trap shaft with tunnel exists (cf. Figure 2). The trap shaft should be darkened so that the amphibians can find the exit more easily. In order to photograph the trap shaft, a wooden board had to be removed (cf. Figure 3). The exit of the tunnel is raised about 20 cm so that it is not used as an entrance (cf. Figure 4).

@ Rieder & Hafner

@ Brenneisen & Szallies

Two-way amphibian tunnels

Two-way amphibian tunnels allow animals to move in both directions. In rectangular amphibian tunnels, the cross-section of the walking surface is usually relatively large (cf. Figure 6), ideally covered with soil materials (cf. Figure 7). A disadvantage compared to the one-way amphibian tunnels with a trap shaft is the possibility in the two-way amphibian tunnels that the migrating amphibians do not find the tunnel entrances. Therefore, it is essential here to provide guidance to the entrances by means of funnel-shaped designs, terrain drops, and/or guide elements transverse to the direction of travel made of boards (cf. Figures 8 and 9), which extend into the tunnel. The larger the cross-section and the shorter the tunnel, the more likely amphibians are to use it. Juvenile amphibians are much more sensitive to the use of tunnels in terms of dryness in the tunnels and finding the entrance. Wooden boards, concrete slabs, metal plates, and probably sometimes plastic plates can be climbed over by juvenile amphibians (cf. Figures 10 and 11) and newts when wet. Overhanging sections are therefore the safest solution best combined with a smooth material. Unnecessary climbing attempts cost unnecessary energy and may reduce survival. On the positive side, juvenile frogs grow quickly and may already be larger when they reach the migration site. Observations in June may indicate if and how the habitat or return migration guidance system should be enhanced.

The amphibian tunnels with the permanent amphibian fences must also be checked. Are the tunnels still passable resp. is the light of the tunnel end still visible? Is there too much snow, leaves, fallen trees or are the amphibian fences otherwise damaged or impaired? Are the tunnels well accepted and quickly found by the amphibians? Are the walking areas along the amphibian fence sufficiently cleared so that amphibians can migrate easily? Are predators causing problems? …

The figure below shows an overview sketch of a two-way amphibian tunnel with guiding devices (cf. Figure 5). The stop gutters (cf. Figure 12 and 13) are intended to keep the amphibians from entering the roads via dirt roads. Whereas these do not always work so well. A cattle grid would be a better option, but is probably too dangerous because of careless pedestrians. Reverse loops (cf. Figure 14) are often missing; they are designed to get amphibians to turn around. Reverse loops should also be installed on temporary amphibian fences.

@ Brenneisen & Szallies

One-way barriers

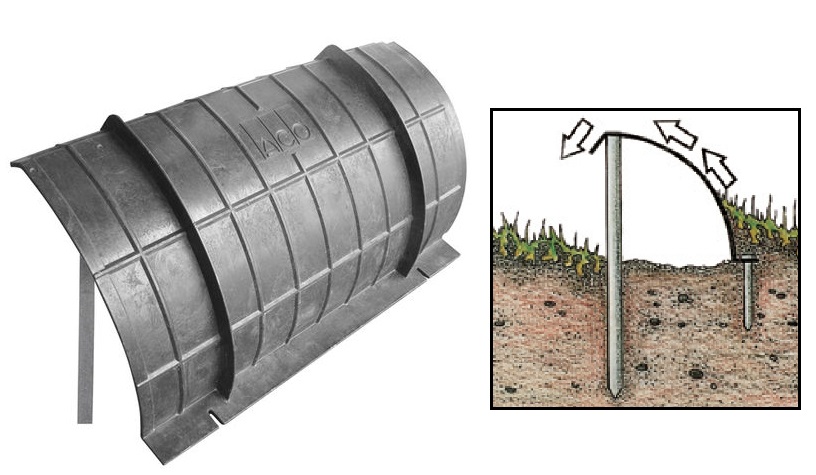

Thanks to one-way barriers, amphibians cannot enter the road from the forest or wetland, but they can enter the forest or wetland from the road. Unfortunately, one-way barriers are not widely used yet. The company ACO offers such “ACO Wildlife One-Way Fences” (cf. Figures 15 – 17).

© ACO AG

© ACO AG

Temporary road closure

A permanent road closure during the spawning season may be a good solution. If this is not feasible, at least a nighttime driving ban should be considered. However, with a nighttime driving ban, a barrier is required that is opened in the morning and closed in the evening. Experience has shown that a no-driving sign and an information poster without a direct blockade are not sufficient. It should be noted, however, that amphibians sometimes migrate in the morning and even in the afternoon. The return migration from the spawning waters, which is usually less concentrated, and the migration of juvenile frogs are often insufficiently protected.